"I love advertisements"

A speach by Mr.Robert(Bob) Gage

A speach by Mr.Robert(Bob) Gage

Seniore Vice President Head Art Directoe, DDB

at Art Director Club of Mountreal 1963

In order to tell you how I like to work, I have to go back to when I first met Bill Bembach. I was working for Kelly Nason, but had decided to quit. Bill was at that time, creative head of Gray. I didn't know Bi1l1 but I had heard that there was a job open and he was the man to see.

I remember the night before I had the appointment with him, I removed everything from my portfolio that showed any compromise. I left only rough comps that I had done on my own which I thought demonstrated the kind of work I wanted to do from here on in.

As I walked in to meet Bill, I had this sudden fear that perhaps the samples I had were too far out, but I still felt that if he didn't like this kind of work, he could lump it, and it was no place for me anyway. I didn't want to do anymore advertising that I couldn't believe in.

Bill went through the work, liked it, and I got the job. Before I left, we discussed the future of advertising.

How he saw it.

How I saw it.

His enthusiasm and his being so articulate had a profound effect upon me.

I had at last found someone who not just tolerated new ideas, but demanded them.

An imaginative writer who thought visually.

That started a wonderful relationship with a man which has lasted and will continue to last for a long time.

When Doyle Dane Bembach started thirteen years ago, working in teams of copywriter and art director was practically nonexistent.

We never worked any other way. I always worked with Bill or Phyllis Robinson in those early

days. A piece of copy was never handed to me. I was never asked to make a layout that had a proconceived idea. I never got those type-written yellow papers with ugly little copywriter drawings on them. I've been very fortunate for the last thirteen years.

It seems to me there's no other way of working.

Of course, you can think alone and start an idea without havinga copywriter present, but actually thinking and conceiving an idea seems to work much better when two people who respect each other sit in the same room for a length of time and arrive at a state of sort of free association, whre the mention of one idea will lead to another idea, and then to another idea.

An art director has to ready to give up a good idea for a better one, and that goes for the copywriter, too. It also doesn't matter, it seems to me, if the copywriter comes up with the visual idea and the art director comes up with the headline.

It's a two man operation right down the line, and the credit for it being a good job should be shared. And if it's a bad job, they've got nobody to blame but themselves.

I've never really cared whether the idea sprang from the copywriter I was working with, or whether it was mine.

Sometimes, I'm put in a position of being a developer of an idea. Sometimes, my contribution is greater. I'm always amazed that I can't trace back the steps that lead to the idea, because the step that was made just before the idea was arrived at is in some foggy section of my subconscious.

Often, we are asked, do we ever get stuck or do we ever run out of ideas.

I must say in all honesty, I had never been stuck, and I have never run out of ideas. But, I must confess that I have had moments or periods in my life and of rrv career where I have

been convinced that I was becoming drained, or that I would never get an idea again.

I now have this pretty well figured out.

I think I know why this happens and I can pretty well forecast when it will happen.

I run, (and I think a lot of our other art directors do too), on kicks. A kick is a way of thinking which seems to be the only way of thinking at the time. No matter how different the advertising ideas are in each of the jobs I work on, this particular kick innuences either visually or in some other way, how these jobs come out.

It soon becomes too easy and I become terribly bored with it.

Then, I'm suddenly pushed into having to find another kick. This is the time when I feel empty, and this is the time when I am depressed. But then I start to climb out of it, and I find that there is a new approach, or a fresh viewpoint. 'then, the cycle starts all over again.

I don't know if it's true, that each time you start to climb, you climb higher. I kind of think it is. I don't think there really is any progress in art, generally, but I do think there is progress within an individual in his ability to express his art.

One of the good things about being in this business a long time is that you begin to understand the conditions under which you work best.

I know that I work best when there is a lot of pressure. Even when a job is not rushed, I seem to procrastinate until it is a rush, because that is the time when the juices begin to flow and I can think better.

I'm somewhat lazy, and I find that this discipline which comes from the outside really helps.

I am not noted for getting 1n early in the morning, but I never think of my job as a 9 to 5 job. When I have a lot of work to do, I would just as soon work all night if I had to.

I also feel that any artist never really gets away from his job.

I try not to bring any particular problems home with me, but it seems to me that the problems of the moment cross my mind and I'm constantly trying to find a solution to one thing or another.

And when I find an exciting solution, I get keyed up and it's hard to think of anything else.

Another thing I find is, that I'm happiest when I have a tremendous amount of work to do.

When I'm busy, I never have time to worry about myself. My mind is on the problem.

And it seems that the more work I do, the more work I'm able to do.

It also speeds up that cycle I referred to before.

You know, when I sit home at night and watch television, (which I sometimes do), and I see the commercials, I get the feeling that commercials, generally, are the biggest bore in the world.

Now I realize that the American economy has to keep moving ahead.

And I realize that advertising is the major tool used by the industries to move their products, but I really feel that you won't move these products by boring people, no matter how many selling points you may jam in.

When I work on a commerical, just the effort to keep from boring someone makes me do better work.

I like people very much. I like them too much to have a cynical approach. To underestimate their intelligence, or to attempt to deceive them.

I've always considered myself an average guy and I feel that if what I do has an appeal for me, other people will be moved by it too.

I've never been able to see things objectively. I'll leave that to the experts. Looking at things objectively, not following your own instincts, destroys your art.

Being artists, we are naturally sensitive to all changes around us. I think more sensitive than most people. If we lose this, we are sunk.

This is the one thing that allows us intuitively to be ahead of the researchers.

One final thing. I think the day is past when the artist who has labored hard and long on his particular piece of creative work has to go to somebody and say, "Here is is, I hope you like it. Please like it. If you don't like it. I'll change it. If you don't like it, I'll shoot myself." The day has finally come, I think, when the people who do the work are also the people who have a strong voice in deciding what work will run.

(The end)

The New Yorker, October 17, 1964

The advertisement for Polaroid "Zoo"

People keep stealing our stewardesses.

Within 2 years, most of our stewardesses will leave us for other men.

This isn't surprising. A girl who can smile for 5 hours and half is hard to find.

Not to mention a wife who can remember what 124 people want for dinner. (And tell you all about meteorology and jets, if that's what you're looking for in a woman.)

But these things aren't what brought on our problem. It's the kind of girl we hire. Being beautiful isn't enough. We don't mean it isn't important. We iust mean it isn't enough.

So if there's one thing we look for, it's girls who like people.

And you can't do that and then tell them not to like people too much.

All you can do is put a new wing on your stewardess college to keep up with the demand.

The New Yorker, May 22, 1965

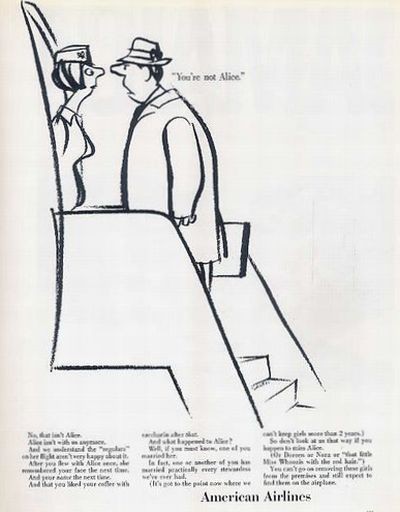

"You're not Alice."

No, that isn't Alice.

Alice isn't with us anymore.

And we understand the "regulars" on her night aren't very happy about it.

After you flew with Alice once, she remembered your face the next time.

And your name the next time.

And that you liked your coffee with saceharin after that.

And what happened to Alice?

Well, if you must know, one of you married her.

In fact, one or another of you has married practically every stewardess we've ever had.

(It' got to the point now where we can't keep girls more than 2 years.)

So don't look at us that way if you happen to miss Alice.

(Or Doreen or Nora or "that little Miss Whoozis with the red hair.")

You can't go on removing these girls from the premises and still expect tofind them on the airplane.

The New Yorker, September 25, 1965

Jamaica Tourist Board

If you can take your eyes off her face for a few moments,

yon may pick up a bargain in silks. Or pedlaps even a Rolleiflcx.

In Jamaica, you have an excuse to stare. Faces like you've never seen before. Shades from a new spectrum. Eyes, cheekbones, skin, lips, hair--- that have always belonged to different worlds. Here, together in one face.

You see a girl behind the counter ofa silk shop. You wonder. How much of that loveliness is Africa? How much

China? How much India? How much Europe? You can't always tell. Sometimes, Africa blends into China into India into Europe. Until the divisions are blurred, the lines of difference, lost. And what comes out is a thing that belongs to none of them. Only to Jamaica. At its best, this new kind of beauty is fragile, dreamy, ethereal. At the yery least, exciting, interesting, unexpected. So who could blame you for not paying attention to the purple silk sari.

But if you can shift your eyes to the silk, you'll see that it is quite a buy. 60% less than you would pay in the States. And those French doeskin gloves. And those Egyptian cottons. 40% less.

Jamaica's duty-free prices are among the lowest in the world. Chivas Regal Scotch, $5.50 a fifth. Seagram's V.O., $2.50 a fifth. 12-vear-old Jamaican rum, $3.00. Aphrodisia-- 60% less. Professional conga drums, hand-made

by Jamaican George Hedley, $22.00. Hand-woven straw bags, $2.50. Nikon, Zeiss Ikon Conta-flex, Rolleiflex cameras, 45% off.

Jamaica? Among other things, it's the world's most beautiful discount house.

For more information about Jamaican eyes, cheekbones or rum, see your travel agent or Jamaica Tourist Board, Dept. 2C, 630 Fifth Avenue, N.Y.C.

With copywreiter Ron Rosenfeld

The New Yorker, November 30, 1963

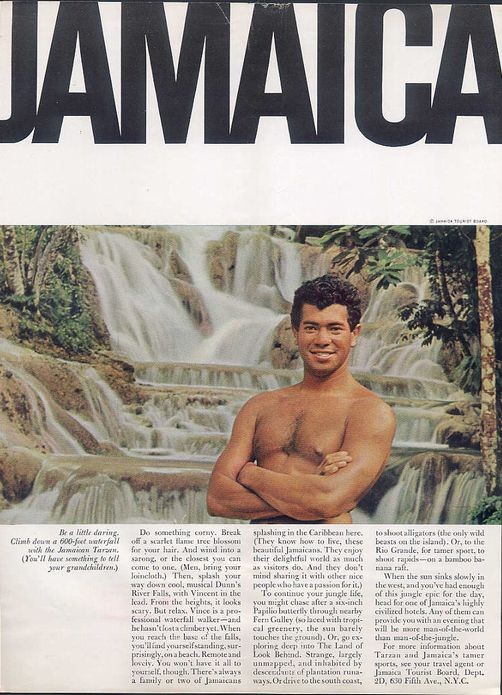

Be a little daring,

Climb down a 600-foot waterfall

with the Jamaican Tarzan.

(You'll have something be tell

your grandchildren.)

Do something corny. Break off a scarlet flame tree blossom for your hair. And wind into a sarong or the closest you can come to one.(Men, bring your loincloth.) Then, splash your way down cool, musical Dunn's River Fall, with Vincent in the lead. From the heights, it looks scary. But relax. Vincent is a professional waterfall walker−−and he hasn't lost a climber yet. When you reach the base of the falls, you'll find yourself standing, surprisingly, on a beach. Remote and lovely. You won't have it all to yourself, though. There's always a family or two of Jamaicans splashing in the Caribbean here. (They know how to live, there beautiful Jamaicans. They enjoy their delightful world as much as visitors do. And they don't mind sharing it with other nice people who have a passion for it.)

To continue your jungle life, you might chase after a six-inch Papilio butterfly through nearby Fern Gulley (so laced with tropical greenery, the sun barely touches the ground). The Land of Look Behind.

Strange, largely unmapped. And inhabited by descendants of plantation runaways. Or drive to the south coast, to shoot alligators (the only wild beasts on the island). Or, to the Rio Grande, for tamer sport, to shoot rapids---on a bamboo banana raft.

When the sun sinks slowly in the west, and you've had enough of this jungle epic for the day, head for one of Jamaica's highly civilized hotels. Any of them can provide you with an evening that will be more

man-of-the-world than man-of-the-jangle.

With copywreiter Ron Rosenfeld

The New Yorker, December 21, 1963

The New Yorker, January 6, 1962

With copywriter Mrs. Philis Robinson

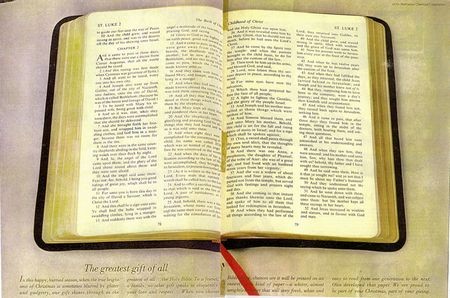

The greatest gift of all.

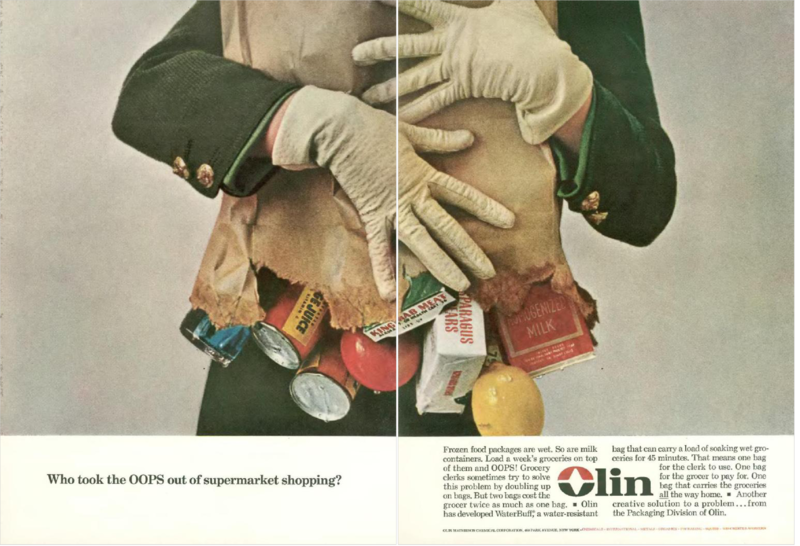

In this happy, hurried season, when the true brightness of Chrismas is sometimes blurred by glitter and gadgetry, one gift shine through as the greatest of all---the Holly Bible. To a friend, to a family, no other gift speaks so eloquently of your love and respect. When you chose a Bible today, chances are it will be printed on an entirely new kind of paper---a whiter, almost weightless paper that will stay fresh, white and easy to read from one generation to the next. Olin developed that paper. We are proud to be part of your Christmas, part of your giving.

I found out about Joan.

The way she talks, you'd think she was in Who's Who. Well! I found ound all those dressest what's what with her. Her husband own a bank? Sweetie, not even a bank account. Why that palace of their wall-to-wall mortgages! And that car? Darling. that's horsepower, not earning power. They won it in a fifty-cent raffle! Can you imagine? And those cloth! Of course she does dress divinely. But really---a mink stole, and Paris suits, and all those dresses---on his income? Well darling, I found out about that too. I just happened to be going her way and I saw Joan come out of Ohrbach's!

advertising layout

Good taste is a volatile thing. What is good taste in one set of circumstances may be bad

taste in another. Taste is even affected by the hands on the clock. Good taste in the morning call bebad taste at night. An art director should therefore, never be self conscious about his taste. It can paralyyze his creativeness. He can live in such fear of offending as to become sterile and passive in his graphic efforts. And, this to me is a greater sin than to be guilty~ of an occasional lapse of manners. Working within the confines of accepted good taste may make an art director feel safe, but that very

feeling of safety may be his greatest obstacle to vitality and originality. If he is to contribute to the growth of graphic communications, he must break through this prison of convention and express himself freely. Good taste can (and often does) make bad advertising.