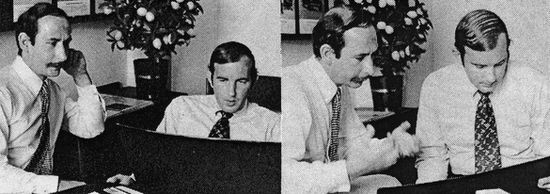

from February 1970 "DDB NEWS"

John Noble Vice President & Copy Supervisor(in 1970)

Roy Grace Vice President & Art Supervisor(in 1970)

(Ed. note - Roy Grace and John Noble have a rare record as a creative team. Every ad and commercial they've done together for Volkswagen has won at least one award - a number have been multi-award winners. Roy started doing VW in 1964, became head art director on the account in 1965. John began copywriting on VW in 1965 and became head copywriter in 1966. While both have worked and do work with others, it was their record together that led the DDB News to interview them as a team.)

INTERVIEWER: What would a creative team prefer - to be assigned to a campaign that is already a classic, or to take on a product badly advertised in the past?

NOBLE: I don't know about preference, but it's easier to make something bad look good than to take a VW campaign and make it better.

NOBLE: I don't know about preference, but it's easier to make something bad look good than to take a VW campaign and make it better.

And I think we made it better. That's harder.

INTERVIEWER: Then why, when Alka-Seltzer came in, was there a stampede by creative people to get onto the account?

GRACE: There's an opportunity that exists in an atmosphere of good advertising.

GRACE: There's an opportunity that exists in an atmosphere of good advertising.

We knew the quality of work the client was used to.

Everybody wants that kind of opportunity.

Also, there's a lot of TV and everybody loves to do TV.

INTERVIEWER: Like VW.

GRACE: Definitely. Same thing.

Both clients are predisposed to a certain level of work.

The size of an account is important too.

When it's big, you get a chance to do a great quantity of work, and it gets lots of exposure.

NOBLE: But anybody in this agency can do one good VW ad or commercial.

The same with Alka-Seltzer.

To sustain it is when it gets tough.

GRACE: It's easy to do a mediocre ad on VW and get away with it, too, because people seeing it will say, "Hey, here's a VW ad, it must be good.

" The important part is not the occasional flash of brightness, but consistency.

To get back to your earlier question, though, I think it's probably more rewarding to take something badly advertised in the past and do something great than to sustain a classic campaign.

INTERVIEWER: Do you get tired of doing VW?

GRACE: Well, I'm primarily on Alka-Seltzer now.

I'm still doing commercials with John for VW, but only on the wagon now.

We finished up as a team on the Bug last month.

NOBLE: I get tired of it, but I don't see anything else I'd rather work on.

And it's a hard account for someone to take over.

There's so much work that people don't see.

We have six A/Ds, and six writers, and we do at least 400 or 500 pieces of work every year - small space, tourist delivery - things people don't see.

Everybody sees Life Magazine or "Jones and Krempler" on TV, but there's an awful lot of other work.

TV-CM of Volkswagen

"Mr.Jones and Mr.Krampler"

INTERVIEWER: What makes you two "work" as a team?

GRACE: I don't know - it's a climate.

INTERVIEWER: You mean that two people create together?

GRACE: Yeah. It's an atmosphere that's conducive to something growing.

INTERVIEWER: How do you know when you're not going to make it with someone you're teamed with?

GRACE: When you don't like what they say and they don't like what you say. When you look at, and communicate, an idea differently.

NOBLE: Sometimes you find out in five minutes and sometimes it takes months, and the months are usually agony.

The best thing to do when you find out is to split.

GRACE: One thing that helps the climate is utmost honesty.

When your partner says something that stinks, you say, "That stinks." You clear the boards.

You don't stand there for half an hour beating around the bush saying, "Well, uh, uh, I don't know, uh, uh."

It stinks, period.

Each person has a veto.

You both have to agree, but it takes only one to disagree.

INTERVIEWER: When you two started working together, did you think, ''Wow, this is terrific"?

NOBLE: It's not like p love affair.

But it's a nice feeling, because after working with people you really DON'T get along with - and they may be very good but there's just no chemistry there - it's good to work with somebody when the chemistry IS there.

And when you can be completely honest.

GRACE: An art director and a copywriter in a good relationship can anticipate what the other is thinking - kind of the way a husband and wife speak in almost a shorthand after years of living together. "Hey"... "ee" ... "ooh " .... " ah" .... and you know exactly what the other is talking about, which is good.

INTERVIEWER: When teams "work", does it matter what kind of product they're on? Whether it's an analgesic or a car or a paper diaper or what?

NOBLE: I think it does, because there are some accounts where there's so much agony that even if you got along well and did great work, after a while the account would wear you down.

And then you start doubting yourselves.

INTERVIEWER: You're talking about accounts. I'm talking about products.

GRACE: I would say some products are easier to advertise than others.

I think cars are easier than soaps.

But then again ... a few years ago somebody would have said suitcases are easier than effervescent tablets.

Until they did the great Alka-Seltzer campaign.

So I take it back. Until somebody makes the great breakthrough, one product SEEMS harder than another.

But there ARE harder client relationships.

INTERVIEWER: Then you wouldn't care what product you were assigned if you thought the client and account men were good?

GRACE: It helps to believe in a product. There are whole areas of products I think are a lot of crap, so I wouldn't want to do them.

I couldn't get involved in them.

I could do on-the-surface advertising for them, but nothing deeper.

INTERVIEWER: What happens to you at cocktail parties when people find out you do the VW ads?

GRACE: I get drunk.

NOBLE: It used to be embarrassing because you always start out doing small space on VW, and people would say, "Did you do 'Think Small' or 'Lemon'?" I'd hide my head and say, "No, but I KNOW the guy who did."

Think small.

Our little car isn't so much of a novelty any more.

A couple of dozen college kids don't try to squeeze inside it.

The guy at the gas station doesn't ask where the gas goes.

Nobody even stares at our shape.

In fact, some people who drive our little fliver don't even think 32 miles to the gallon is going any great guns.

Or using five pints of oil instead of five quarts.

Or never needing anti-freeze.

Or racking up 40,000 miles on a set of tires.

That's because once you get used to some of our economies, you don't even think about them any more.

Except when you squeeze into a small parking spot. Or renew your small insurance.

Or pay a small repair bill. Or trade in your old VW for a new one.

Think it over.

"Life" August 6th, 1967

A/D Helmut Krone

C/W Robert Levenson

Lemon

This Volkswagen missed the boat.

The chrome strip on the glove compartment is blemished and must be replaced. Chances are you wouldn't have noticed it; Inspector Kurt Kroner did.

There are 3,389 men at our Wolfsburg factory with only one job: to inspect Volkswagens at each stage of production. (3000 Volkswagens are produced daily; there are more inspectors than cars.)

Every shock absorber is tested (spot checking won't do), every windshield is scanned.

VWs have been rejected for surface scratches barely visible to the eye.

Final inspection is really something! VW inspectors run each car off the line onto the Funktionsprufstand (car test stand), tote up 189 check points, gun ahead to the automatic brake stand, and say "no" to one VW out of fifty.

This preoccupation with detail means the VW lasts longer and requires less maintenance, by and large, than other cars. (It also means a used VW depreciates less than any other car.)

We pluck the lemons; you get the plums.

A/D Helmut Krone

C/W Julian Koenig

But now, I kind of enjoy it.

They say, "Did you do the commercial with the two houses, Mr. Jones and Mr. Krempler?"

I really eat that up. "Yeah, I did."

I finally can say yes.

Because for a couple of years I always had to say no.

GRACE: I try to hide it. I don't want anybody to know. I find it boring to talk about. You live with the damned thing so much, you'd rather talk about someth ing else at cocktail parties.

Especially when you get the kind of question like "How do you do a commercial?"

It really bores the hell out of me.

INTERVIEWER: You say. you live with it. Do you always have problems churning inside to which solutions pop out at odd times of the day and night?

NOBLE: You really don't ever stop thinking about it.

The train is a good thing.

You have nothing else to do on a train.

And when I go to bed it's the last thing I think about.

Sometimes. And when I wake up in the morning, it's the first thing.

And that's what's great about working with someone.

You go to bed at night loving a concept you've thought of that evening.

You get up in the morning, you're less sure of it.

By the time you get into the office, you really think it's terrible.

But at least you have somebody you respect to try it out on.

It's very hard to kill your own things...

GRACE: I hate to say this, but when I'm shaving ... Everything comes together from the last few days and the night before.

It's like integrating all the little pieces ... I guess that's how an idea is created.

And as you're shaving you suddenly say, "Oh, my God, that's terrific!" and you can't wait to shave, and you can't wait to get to the office, and you can't wait to do it.

That, to me, is the most exciting part of the work − the idea.

When it first comes it's like a brilliant ray of light.

After that, it's downhill.

NOBLE: That may explain the talents of some A/Ds I know with beards.

INTERVIEWER: About the flash of light ...

GRACE: I'll tell you what it's like ... let's say John said "One" last week.

A day later I said "Three." And then he said "Four." You've got to reach the number Ten.

Then all of a sudden the missing piece that binds it all together, that makes it add up to Ten, comes, and it's like hitting a magic spark.

You know it's going to work.

You know it's right.

Then the problems come ... in trying to execute the idea so that it comes off right.

You CAN lose it in the execution.

INTERVIEWER: Let's talk for a few minutes about something I know you two feel strongly about - fighting for your ads.

GRACE: Yes, I think 50 percent is doing the work, and 50 percent is fighting for it.

Fighting for what you believe in.

Too many people are willing to do the work, but at the first No they surrender.

You can be the greatest talent in the world, the greatest team doing the greatest work, but if you're not willing to

defend it, it'll never see the light of day.

NOBLE: There are account men who can talk young creative people out of a concept very easily.

But if it's been approved by the Creative Department, that means it ain't a bad ad when it goes up there.

There may be certain problems, but for creative people to come back immediately after seeing an account man and say, "We can't do this because so-and-so says we can't do this," is wrong. There should be a battle.

INTERVIEWER: Why do you think there isn't a battle?

GRACE: Insecurity, probably. But when an AID and writer think a concept is right enough to spend 20 hours on, they should be articulate enough and have the tools to be able to convince the account man it's right.

Or at any rate he should prove they're wrong rather than saying he won't buy it.

It's not his prerogative to "buy" an ad.

His job is to sell an ad.

But it's really the fault of the AID and writer because of their passivity - and their lack of equipment.

NOBLE: And this is where your team thing comes in too, because there's nothing worse than going to an account man's office - it's two against one in your favor - and after five minutes one of you says "Yeah, he's right."

Because then you're destroyed.

GRACE: If the account man can convince them they're wrong in five minutes, they should never have been up there with t.hat ad.

Either that ad is all wrong, or they're all wrong. They failed in one area or the other.

NOBLE: Supposedly when you .90 up there you know all the client's problems, all the problems relating to that ad.

If the account man has done his job beforehand, he has told you everything that has to do with that ad.

That means, you being the professional creative man, when you go back to him with your ad, that ad should be right.

GRACE: You should bat about 80 percent.

There are times when you make mistakes, and times when there's something you don't know.

But 8 out of 10 times you should be right on the button.

Or there's something wrong with the team.

Either they're not good enough - they don't have the talent - or they don't understand what they're doing.

Or they're just afraid.

An account man said no because, while the ad may be very good it may be too controversial, and he doesn't want to give himself a headache.

This is where the creative team should say, "That's your problem, not mine; that ad is right."

But they should know why it's right just as the account man should be expected to say what makes it wrong.

It's a matter of life and death - the life or death of the ad - and the team should be willing to put everything they've got behind it.

After we pant the car we paint the paint.

You should see what we do to a Volkswagen even before we paint it.

We bathe it in steam, we bathe it in alkali, we bathe it in phosphate. Then we bathe it in a neutralizing solution.

If it got any cleaner, there wouldn't be much left to paint.

Then we dunk the whole thing into a a vat of slate gray primer until every square inch of metal is covered. Inside and out.

Only one domestic car maker dose this. And his cars sell for 3 or 4 times as much as a Volkswagen.

(We think that the best way to make an economy car is expensively.)

After the dunking, we bake it and sand it by hand.

Then we paint it.

Then we bake it again, and sand it again by hand.

Then we paint it again.

And bake it again.

And sand it again by hand.

So after 3 times, you'd think we wouldn't bother to paint it again and bake it again. Right?

Wrong.

TV-CM of VW beetle "Funeral"

art director:Roy Grace(DDB)

copywriter:John Noble(DDB)

director:Haward Zieff

producer:Don Traver(DDB)