Writing Fiction is Harder,

Says Jack Dillon(2)

Vice President, Copy Supervisor of DDB(in 1968)

Interviewer: Where did you work before you came to DDB?

Dillon: I was at Fuller &Smith & Ross for 10 years.

It wasn't one of the creative shops, but you got to know a lot about the business, including a lot of ways to come up with an ad when somebody said they needed it in an hour.

What you do in a case like that is go by the book.

Interviewer: An ad in an hour? What's the book?

Dillon: The basic rules of copywriting have been written up a dozen times I guess, and they're still valid. You get the consumer's attention by offering him a benefit, you repeat the

benefit in the beginning of your copy, expand on it a bit, and explain how this benefit comes about.

Then, if you have time, you bring out the losses he'll suffer without this benefit, then repeat the benefit and ask him for the order.

Then, if you have time, you bring out the losses he'll suffer without this benefit, then repeat the benefit and ask him for the order.

This is a grocery list, and we depart from it very often.

But it's very good to know that this grocery list exists.

You ought to know what the rules are before you throw them out.

Interviewer: Those are the copy rules, what's your method for implementing these rules?

Dillon: When I sit down to write an ad and don't know quite where to start, I'll tryout 10 or 15 different headline approaches to either get them out of my system or see if one of them fits the problem.

Once I've found an approach that seems to me to work, then I'll go back and look for a way to make that approach different and dramatic.

If you have a sound, strong proposition that amounts to news like 50% off on brand-new Buicks, nothing should keep that news from getting to the reader.

That's more important to him than any lesser thing you might bring up. You might find a more adroit way of saying it "50 percent off on brand-new slightly scratched Buicks," for example, does something else for the ad. It

gives the reader a reason for believing you.

The thingis, if you have a straight, sound piece of news that's what your ad should be.

If you have a thin proposition that the client insists on promoting, humor is often a way of doing this so that the thinness does not become apparent to the reader.

And it can also get you some residual effects of good feeling for-the company that ran the ad.

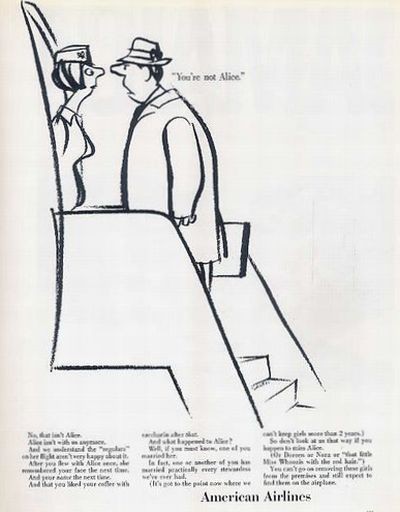

Interviewer: Was this the rationale behind the Saxon cartoon campaign for American Airlines?

Dillon: No, American had a great many things to say. But there was no basic underlying theme.

The Saxon cartoons, the look and tone of voice of the ads, was what tied the ads together.

"You're not Alice."

No, that isn't Alice.

Alice isn't with us anymore.

And we understand the "regulars" on her night aren't very happy about it.

After you flew with Alice once, she remembered your face the next time.

And your name the next time.

And that you liked your coffee with saccharin after that.

And what happened to Alice?

Well, if you must know, one of you married her.

In fact, one or another of you has married practically every stewardess we've ever had.

(It' got to the point now where we can't keep girls more than 2 years.)

So don't look at us that way if you happen to miss Alice.

(Or Doreen or Nora or "that little Miss Whoozis with the red hair.")

You can't go on removing these girls from the premises and still expect to find them on the airplane.

Interviewer: Apart from knowing the rules, and having a method, what else should a young writer know about coping with writer's block?

Dillon: The first thing a young copywriter who runs into a block should dais forget writing, and write the ad just as fast as he can.

Forget how it's written and just get a progress of thought down on paper.

Forget whether the words are good or bad.

He may surprise himself when he's through and find out that he's got a swell piece of copy.

It's very possible to get hung up on the first sentence and on whether or not the second sentence meshes beautifully with the first. As a consequence, you're so busy meshing sentences together that you never get a piece of copy that works.

The same thing is true in fiction. You can get so hung up on how the first sentence on the first page reads that you'll write 400 first pages, keep rewriting them and never get the book down.

I think to an extent the same is true of writing copy.

If you get a block, just sit down and write a straight piece of copy, and forget how it reads.

Get your thought processes in order.

If you don't even have an idea, start with the very basics and go from there.