Presended at the Eastan Annual Comnference

American Association of Advertising Agencies

Copy & Art Section

November 14, 1962

Americana Hotel

New York City

The Way Of Working That Works For Me (3)

The Way Of Working That Works For Me (3)

by STEPHEN O. FRANKFURT

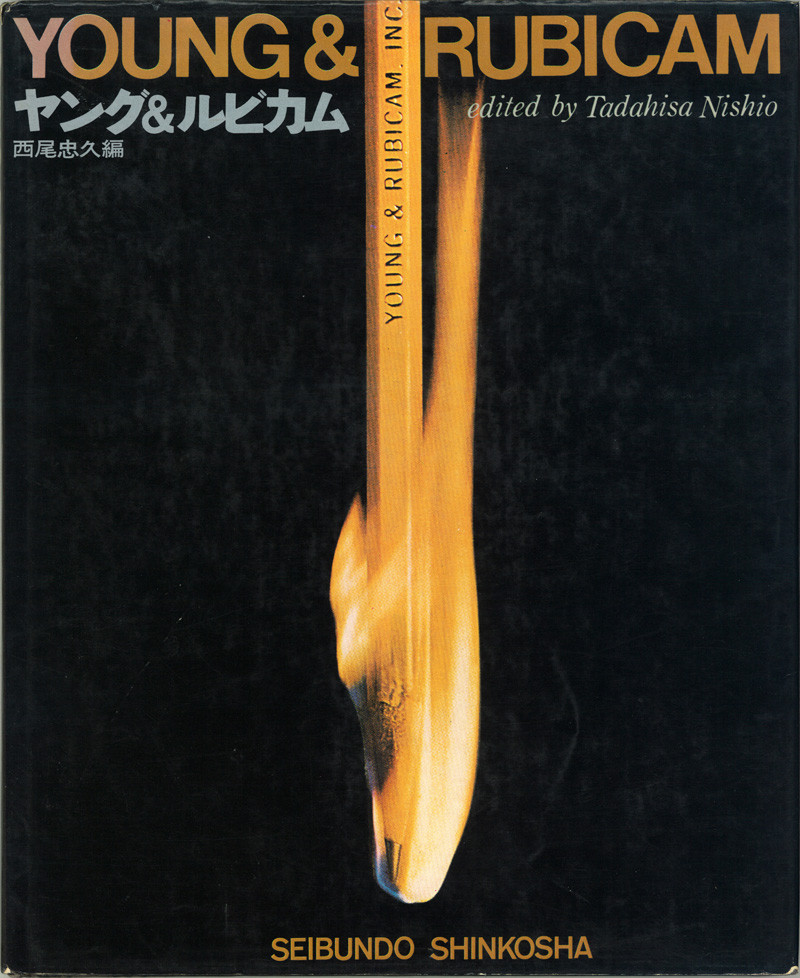

V. P. Executive Art Director Young & Rubicam, Inc.

Which brings us to what might be called the third

or PROJEOTION PHASE in solving a problem.

PROJEOTION, as I'm using it here, is the conscious

process-the process of projecting what you.

already know, towards solving the problem at hand.

Up until this point, we've been working ina nan

rational way. By non-rational, I don't mean ir-ra-

tional. But the time comes when you .can no longer

push papers or write personal letters, or make urgent

phone calls to your stock broker.

The time comes when you must apply the seat of

your pants to the seat of your cha,ir, and consciously

and rationally focus in on the problem.

There are many people in our business who are

intolerant of what they think of as "procrastination".

As a matter of fact, the most intolerant are usually

the supposed "procrastinators" themselves. lost

creative people and I'rn excluding hacks――would

admit that they procrastinate. I'm sure there are

many in this room who consider themselves procrastinators.

I don't believe it. I don't think the early period of

Ingesting a problem and information; and then

Digesting its significant elements,arepro'crasti:nation.

During this period, nothing is put on paper to

prove you've been working. So what can you believe,

except that you've procrastinated? Not so. The

solution has been fermenting.

In answer to Bill Bernbach's question, "What do

you do when you get stuck?" I walk around the problem.

I lookat it. I talk about it. I go for a walk.

I forget it. I go home and play with the kids. I go

to the rnovies.

Up Untill the Projection phase, when you tackle

your problem systematically, none of your thoughts

or observations. may have. seemed relevant to the

solution.

But now the mind starts to look for relevance.

It JutinouJ the mind stats to look Jorrelevance.

It starts to narrow down the search.

And here's where you separate the men from the boys.

This phase of creating takes discipline.

And i'ts painful.

It calls for total application of the disciplined

self to start putting something on paper.

All of us have our ups and downs.

And the downs often come when a work block sets in,

when you get to a pointin the problem-solving where you

don't believe you have an idea, and you're convinced one

will not be forthcoming.

One way to start dissipating the block is to narrow

down the focus.

I know a writer who doesn't need glasses.

She has a pair of reading glasses which shewears

occasionally for reading very fine print.

But when she gets ready to put so mething on

paper, she puts on the glasses, which don't do a

thing for her vision, but she says it helps her to

close out everything around her which does not

fall within the limited range of the eyeglasses.

One of the Art Directors in our department tells

me that when he feels ready to start drawing, he

cleans everything out of his office that is not directly

connected with the assignment.

I always know when he's about to show up with a stack of

layouts because his wastebasket is filled with old magazines

and unread Contact Reports. Just as it's important to see-all

and hear-all during the early stages of the creation

process, so is it often helpful to see little and listen

to little that can distract you once you have really

started to put sornething on paper.

If it were up to me, I'd equip every Copywriter's

and Art Director's phone with a shut-off button,

so that they could turn it off completely when ready

to write or design.

This brings us back to such questions as these:

"Does night work payoff?" and "Do you do your

best work in the morning, or the afternoon, or after

hours?"

I do my best work when I have to; when there's

a call for it.

So does any professional.

I think it was Richard Rodgers who was asked when he wrote

his songs.

He, too, said, "I write them when I have to."

Now this may sound like a negation of everything.

I've been saying, but it isn't.

The phases of problem-solving I'm describing could take days or

even weeks or, in some rare instances, months.

But the entire four-phase cycle could also be telescoped down to

a matter of hours, or an hour, or even minutes.

The mind has the ability to jump hurdles with

amazing speed, and when the pressure is on and

the adrenaln is working――and, of course, provided

that the WrIter or Art Director has a professionalism

billt of experience, talent, and intuition-then

the solution can come qickly.

In fact, many creative people express surprise when

the first idea they come up with turns out to be the

best and most usable idea of all.

But that "first idea" didn't come out of a vacuum.

It comes by messenger from the well of knowledge

previously accumulated.

To return to the question, "Do you do your best

work in the morning, afternoon or after hours?" let

me say that it doesn't matter what time of day

it is, or what time of night, for that matter.

Once I start putting it down on paper, I don't want to

stop.

We are not an agency that keeps our people chained

in the cellar at night, with a keeper who comes around

and whips them at half-hour intervals.

But I would like to suggest that once you're moving,

don't break the pace.

If you do, just because it's five o'clock, then you have

to start all over again in the morning, getting the right

mind-set, and reorienting yourself to the problem.

It could work this way.

But usually, the first two phases work concomittantly.

And sometimes, the first three phases are all going on at

the same time.

to tomorrow.

Ads Series for Sony TV on [New Yorker's Archives](An index) ←clickAds Series for Chivas Regal on [New Yorker's Archives](An index) ←click

Ads Series for Avis Rent a car on [New Yorker's Archives](An index)←click

Ads Series for VW beetle on[New Yorker's Archives](An index)←click