An Interview with Helmut Krone (completed)

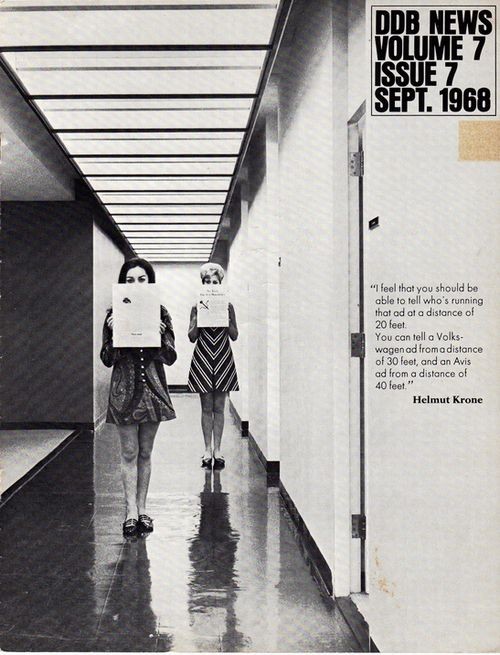

Cover of 'DDB NEWS' in November issue, 1968 in which interview of Mr.Helmut Krone.

Mr.Krone talked however by this interview because the advertisements of Avis of 'big copy and small picture' parted 30 feet that the advertisement of the Volkswagens of 'big picture and small copy' is able to recognize 20 feet.

INTERVIEWER: Is it true that you are a perfectionist?

KRONE: I resent the charge.

A perfectionist is someone who finishes the backside of a drawer, which I consider completely unnecessary.

I spend a lot of time on the front, but I am definitely not interested in the backside of the

drawer.

I feel that there's this imaginary line, and you have to get over that line.

As soon as I feel I'm over that line, I quit.

I don't go any further.

I'll leave a thing without all the ends pulled in as soon as it's over that line.

INTERVIEWER: You mean you have a certain standard and when- you reach it, you stop.

KRONE: Yes, just like everybody else.

Now, maybe that line is in a different place for me.

It all depends on where you place that line.

For example, in engravings or television production I feel that I'm not a stickler no matter what anyone says.

If the page has the effect I was after, I'm not interested in petty little corrections.

INTERVIEWER: How did you come to work on Volkswagen when DDB first got the account?

KRONE: I got on Volkswagen because I was the only one who'd ever heard of the car.

I had one of the first Volkswagens in the United States, probably one of the first hundred, long before I ever worked here.

And just to show you how wrong a person can be - and how fallible I am - I was dead set against the Volkswagen campaign as we did it.

I felt that the thing to do with this ugly little car was to make it as American as possible, as fast as possible.

Like, let's get Dinah Shore also.

What's that thing she used to sing? "See the USA in your Chevrolet"

I wanted "See the USA in your Volkswagen." With models around the car and TV extravaganzas.

INTERVIEWER: But it was on Volkswagen that you chnged the look of ads. You changed the way the copy looked.

KRONE: Well, first let me say that on Volkswagen I felt so strongly that we were doing the wrong thing - even though I contributed my

third to it, certainly - that I finished up three ads, went on vacation to St. Thomas, depressed, came back two weeks later, and I was a star.

INTERVIEWER: You say you contributed your third. Not your half?

KRONE: My third, Bill Bernbach's third, and Julian Koenig's third.

INTERVIEWER: What was Bill Bernbach's third?

KRONE: Mostly in keeping me from doing the other.

Also, the whole concept of speaking simply, clearly and with charm belongs to him.

There was nothing new about the Volkswagen idea, the only thing was that we applied it to a car.

Probably eight years before that, Bernbach did an ad for Fairmont strawberries where he showed a

whole strawberry in the middle of a big page, just one life-sized strawberry.

And the headline was: "It seemed a pity to cut it up." What they were selling were the only whole frozen strawberries on themarket.

The point being that a strawberry has to be perfect ~ in order to keep it whole.

Volkswagen is not any different from that ad that he did a long time before.

The only thing different about it was its application to carsand that's different enough.

I took traditional layout A, which kad always existed: 2/3 picture, 1/3 copy,

three blocks with a headline in between.

But I changed the picture.

The picture was naked-looking, not full and lush.

The other small change was the copy, which was sans serif rather than serif.

INTERVIEWER: And nobody'd ever done that before?

KRONE: Not with that layout, no. It was an editorial look, but with sans serif type.

INTERVIEWER: And nobody'd ever done that before? ?

KRONE: Not with that layout, no. It was an editorial look, but with sans serif type.

INTERVIEWER: The look of the copy was very different. The use of "widows" which we spoke of once before.

KRONE: I actually cut those "widows" into the first Volkswagen ads with a razor blade and asked

Julian Koenig to write that way.

I deliberately kept the blocks from being solid, and when I felt that a sentence could be cut in half I suggested it just to make another paragraph.

I wanted the copy to look Gertrude Steiny.

The layout in that case actually influenced a new copy style, which Bernbach later referred to as "subject, verb, object."

INTERVIEWER: You mean the layout came before the copy style? The copy style came about because of the way it would look on a page?

KRONE: Definitely.

Before then, it was usually the art director's job to get writers to fill out "widows," so that they could have a neat, No.2-looking gray wash on the page.

As far as layout is concerned which I consider a lost art - I feel that almost no one is looking around for a brand new page, a new way of putting down the same old elements, a new way of breaking up that 7 x 10 area.

INTERVIEWER: You're sayIng that they should be.

KRONE: Yes, but everybody wants to belong to the current club.

There's safety in that, I suppose.

And they want to show they're smart enough to recognize what's good, what's "in."

They think being current, being fashionable is being new.

And it's really the opposite of new.

If you get a medal in the Art Directors Club, the chances are that what you did was not an innovation.

I'd say that about almost every medal that I've gotten.

They were for innovations that were already a year or two old, and, therefore, easy to digest.

If people say 'to you "that's up to your usual great standard" then you know you haven't done it.

"New" is when you've never seen before what you've just put on a piece of paper.

You haven't seen it before and nobody else in the world has ever seen that thing that you've just put down on a piece of paper.

And when a thing is new all you know about it is that it is brand new.

It's not related to anything that you've seen before in your life.

And it's very hard to judge the value of it.

You distrust it, and everybody distrusts it.

And very often it's somebody else who has to tell you that that thing has merit, because you have no frame of reference, and you can't relate it to anything that you or anybody else has ever done before.

Alexey Brodovitch at the New School was the one who put me on to "new." Students would bring in something to class that they thought was spectacular, but he'd toss it aside and say: "I've seen this once before somewhere."And he wouldn't even discuss it.

INTERVIEWER: What was his reaction when you did something he'd never seen before?

KRONE: I never did anything he'd never seen before while I was in his class.

I wasn't ready.

And now that I've done all that talking about "new" let me contradict myself and take a swing at the current trend toward "doing your own thing."

I asked one of our writers recently what was more important:

Doing your own thing or making the ad as good as it can be.

The answer was: "Doing my own thing."

I disagree violently with that.

I'd like to propose a new idea for our age: until you've got a better answer, you copy.

I copied Bob Gage for 5 years.

I even copied the leading between his lines of type.

And Bob originally copied Paul Rand, and Rand first copied a German typographer named Tschichold.

The thing to do when you get a requisition is to find an honest answer. Solve the problem.

Then, if through the years a personal style begins to emerge, you must be the last to know.

You have to be innocent of it.

INTERVIEWER: I'd wanted to ask you about the Avis layout....That was new too, wasn't it?

KRONE: Yes. I remember going home on the train one night with Bob (Gage).

Everybody at that time was doing Volkswagen layouts.

In fact, the headlines were getting smaller and smaller, and the fashion at the time was to write three meaningful words, so strong in themselves that you could set them in very small type.

And we had a discussion about this on the train, and he said: "How much smaller can headlines get before they become invisible?"

And I thought about it. I was working on Avis currently and looking

for a page style.

Now that's very important to me, a page style.

I feel that you should be able to tell who's running that ad at a distance of 20 feet.

INTERVIEWER: Just by the page style?

KRONE: Just by the page style.

You can tell a Volkswagen ad from a distance of 30 feet, and an Avis ad from a distance of 40 feet.

Anyway, to get back to this headline thing.

I started thinking about what he'd said, how absurd it was getting with these headlines getting smaller and smaller.

So what I did was I took the Volkswagen style and turned it inside out: the headline became big, and not in the middle, I put it on top.

The picture became small, and the copy became large.

It was very carefully, methodically done, very coolly arrived at.

It was not inspired.

It was a mathematical solution.

I made everything that was big, small, and everything that was mall, big.

KRONE: Why don't you come clean and ask me why I'm so slow.

INTERVIEWER: O.K. Why are you so slow?

KRONE: I have no defense, only a reason.

Though a New Yorker, I had a German upbringing.

And I'm the recipient of the best of such an upbringing as well as the victim of the worst part of it.

A German son is always wrong until he's proved himself to be right.

He is a knownothing and has everything to prove.

It gives you a certain insecurity which is the opposite of "chutzpah."

You tend to rework things and believe they're never good enough, because,

after all, you're a "knownothing."

David Ogilvy once said: "An agency ought to be on time, just like a good tailor."

But in defense, I'd like to say that I've got the best tailor outside of Rome - and he's always late! <I>INTERVIEWER: Do you enjoy it, the work?

KRONE:KRONE I don't know.

I go back and forth.

Advertising is stupid.

Advertising is great.

Advertising is totally unnecessary.

Advertising is the most vital art form of our day.

It depends on what week it is.

I think they're both true.

I didn't plan out my existence.

"I'm going to do this for two years, this for three years, and then I'll be

a vice president, and so on."

I never heard of stock options.

All I did was keep my nose on the board.

I worked my ass off.

I worked just like my father and mother worked.

My father was an orthopedic shoemaker and my mother was a seamstress, and I believe that they were probably the best shoemaker and seamstress in America.

I believe that with allmy might.

And I guess that's how it all happened.

They used to work their heads off.

And people said they were the best.

Interviewer: Sandra Karl